god, whose memory holds the future

I visited Yale Divinity School on September 25, 2016 and had the opportunity to lead music and offer a short sermon for a Eucharist service focused on Psalm 137. A refrain was woven through the text, based on the hymn tune EBENEZER which was taught without paper.

God whose memory holds the future,

God whose mercy holds the past,

God whose listening is our present,

You will bring us home at last.

- Richard Leach, © 1996 Selah Publishing Company, Inc.

from Psalms for All Seasons

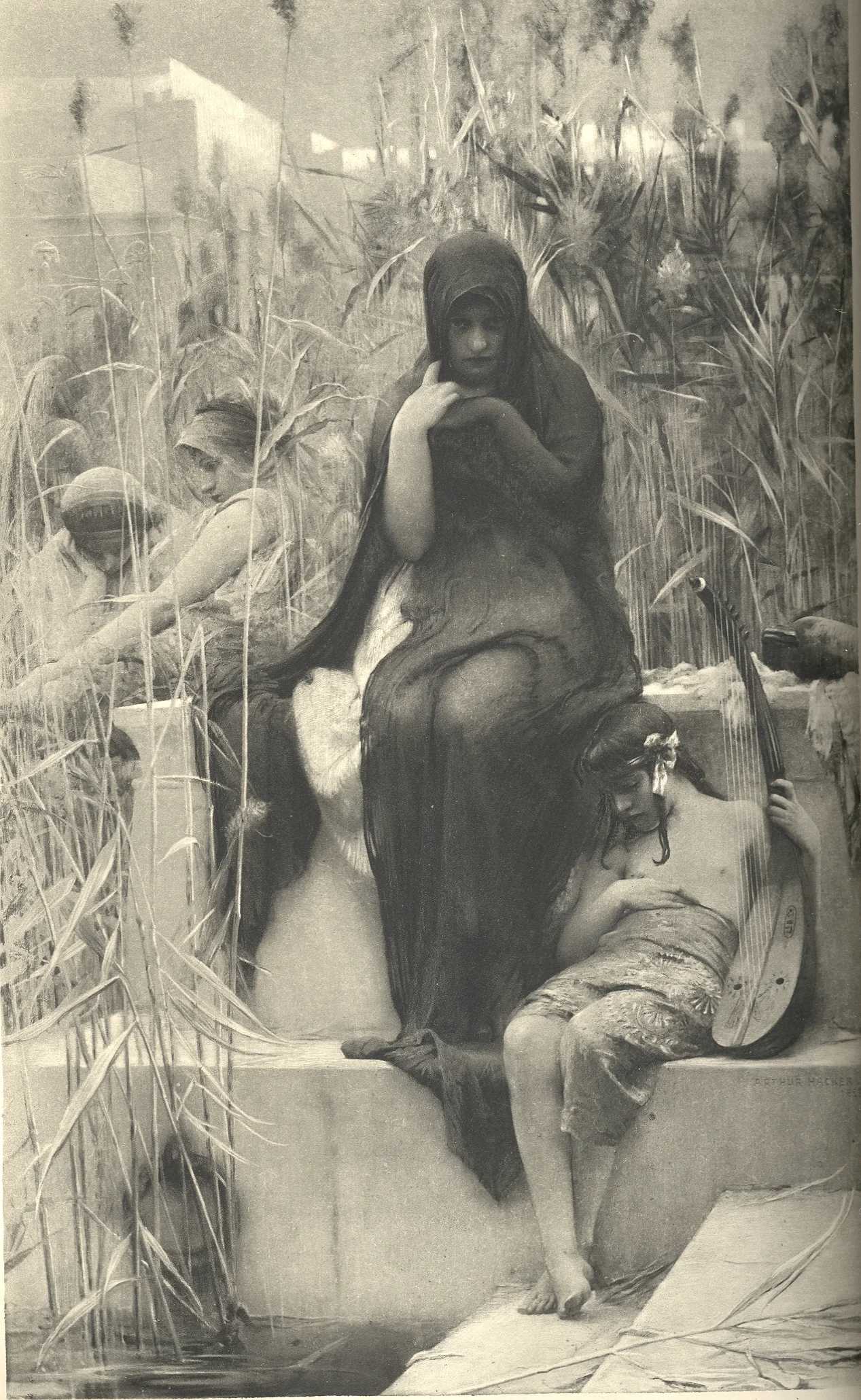

I wonder if Psalm 137 shines light on the way that communities hold trauma, anxiety and grief, even in ways we may not fully aware of? I don’t believe this psalm is inviting us to some sort of catharsis. I don’t feel better after praying these words; they make me uneasy, even nauseous. They read like a person with PTSD who has been triggered by a loud sound. All the images come rushing back in a way that disorients and jangles the nerves. I hear no comfort, nothing pastoral; only an unsettled reminder of just how difficult and messy life can be.

Trauma does strange things to us. It separates us. It can estrange us from our very selves and make us strangers to each other. Even if we haven't experienced it personally, we can feel collectively scattered, our thinking becomes clouded and we can be less conscious of, or engaged in, the life around us. We may function but we’re living in a kind of fog. And this prevents us from seeing each other clearly, which can lead to suspicion, distrust, and aggression.

Maybe the most recent experience of this kind of collective trauma was after 9/11. I remember the congregation I served in St. Louis singing the haunting paraphrase of Psalm 137, By the Waters of Babylon, at a prayer vigil the very evening of the attacks. I remember the sad, blank stares in the supermarket in the weeks following and the shroud of grief that seemed to take years to lift. But I also remember how quickly our collective trauma turned to retribution, to rage against supposed perpetrators of violence.

We might wince or grimace at the last line of the Psalm (those uncivilized, ancient people) but in the years following we dropped thousands of bombs on innocent civilians in Iraq and Afghanistan, including children. Is that any different from dashing their heads against a rock? Was our motivation any different?

Maybe Psalm 137 reminds us that the distance between victim and victimizer is uncomfortably close. Our untended grief and anger can easily cause us to act violently toward others. And as we know from wars waged since 9/11, the destabilizing cycle of violence only continues in an endless, chaotic pattern.

And it’s not just in the past. We hold other places of collective trauma and pain right now, this week… systemic and individual racism that leads to devaluation and murder of black and brown lives, religiously sanctioned bigotry and hatred, unvarnished misogyny in politics, transphobia, corporate greed, continued bias against and distrust of immigrants, migrants, and refugees…

God whose memory holds the future,

God whose mercy holds the past,

God whose listening is our present,

You will bring us home at last.

In my ongoing work as an interim/transitional musician, I frequently encounter communities that have experienced or are in trauma. Sometimes it stems from the loss of a beloved musician who is terminated or retires, sometimes from misconduct or abuse, or the messiness of undifferentiated or codependent leadership, which might seem less severe but still has serious casualties.

What I have noticed is that a community’s negative, painful experiences are often channeled in two, often opposing directions:

1. anxiety about the future – How will we survive?

2. focus on the past – Remember when?

What can be most difficult for communities in trauma or transition is being fully present in the moment – taking stock of what they feel and see right now and giving it voice.

One tool that has helped these communities become more aware is singing, especially the style of paperless singing that you’ve seen modeled today and that I learned through Music That Makes Community. This work invites us to notice what happens when we learn together, sing together, and even move together. It invites us to a different kind of listening than we might do when we have music in our hands. It invites us to find connection to others through our faces, gestures, voices, and bodies, and deepens our sense of community.

As I invite congregations into this practice of singing together, I notice that something starts to shift. It’s not that estrangement, anger, grief and other difficult experiences disappear. Yes, our experiences are given voice in the music we sing and sometimes it is cathartic. But more practically, participatory singing invites us into communion with people of varied ages and abilities, with complete strangers, or even folks with whom we disagree.

Because authority is shared by the group and not held by only one person, relationships can be quietly negotiated and renegotiated through sound. I have also noticed voices that have been silent or silenced (people the community has never or rarely hears from) are emboldened, and the perspectives or nuggets of wisdom they share can help the community to see itself in a new way.

When we sing without paper, we don’t just invite folks to sing along, to a novel way of learning together, or a more palatable alternative to praise and worship music. But we hope and pray that this type of singing together leads to fresh perspectives, integration of body, mind, spirit, and voice…to an appreciation for wholeness in place of perfection.

At the heart of the work is contemplative spiritual practice. Singing together is the medium through which we practice holding the beauty and the messiness in a gentle, gracious embrace, trusting that beyond us or below us is some deeper Love or Wisdom that holds us and holds everything in care.

I’m grateful for Richard Leach’s surprising paraphrase of Psalm 137, an excerpt of which has framed the sermon this morning. It speaks to the power of being in the moment, even in face of challenges and trauma. In his words I hear trust in a God whose memory is so comprehensive and all-inclusive that it even holds the future. It speaks of a mercy that doesn’t heal the past but holds it.

In this paraphrase, I hear striking words about a God with us in this very moment, modeling what it means to be an active, listening presence. While the hurt and grief may never be healed or resolved in the way that we anticipate or imagine, we hold onto hope that we will return back to a place of safety and wholeness, either in this life or in the life to come.

Maybe as we practice being fully present to the moment, not rehearsing a wounded past or anxiously awaiting an uncertain future, we will find an enduring sense of peace, of at home-ness, both in our selves and in each other? May it be so.

God whose memory holds the future,

God whose mercy holds the past,

God whose listening is our present,

You will bring us home at last.